Instruction selection is a critical component of compilers, as different instructions can cause significant performance differences even when the semantics remain unchanged. Does register selection also affect performance (assuming the register selection does not lead to more or fewer register spills)? Honestly, I never intentionally thought about this question until I came across it on Zhihu (a Chinese Q&A website). But this is a really interesting topic that touches on many tricks of assembly programming and compiler code generation. So it deserves a blog post to refresh my memory and share my thoughts :)

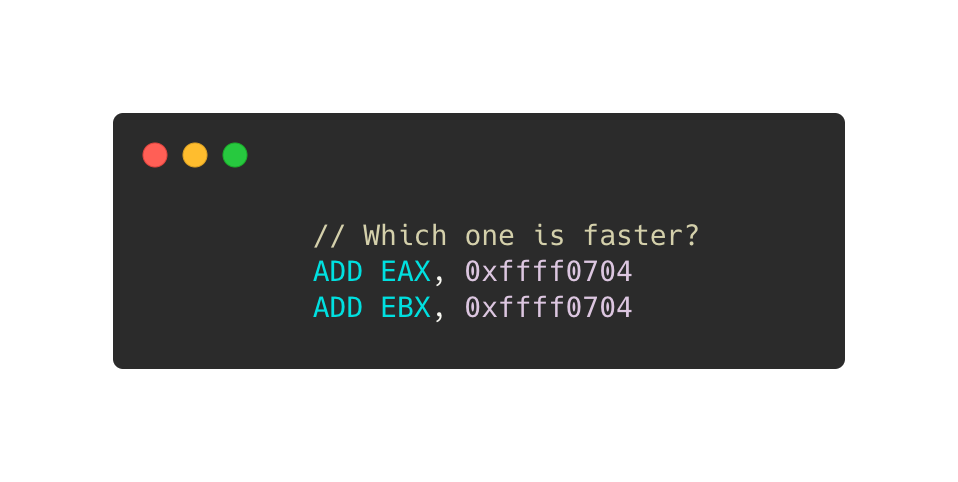

In other words, the question is equivalent to

Is one of the instructions below faster than another one?

And the question can be extended to any instruction of x86/x86-64 ISAs (not only on ADD).

From undergraduate classes in CS departments, we know that modern computer architectures usually have a pipeline stage called register renaming that assigns physical registers to the logical registers referred to in assembly instructions. For example, the following code uses EAX twice but the two usages are not related to each other.

ADD EDX, EAX

ADD EAX, EBXAssume this code is semantically correct. In practice, CPUs usually assign different physical registers to the two EAX usages to break the anti-dependencyADD EAX, EBX does not have to worry about whether writing to EAX affects ADD EDX, EAX. Therefore, we usually assume that different register names in assembly code do NOT cause performance differences on modern x86 CPUs.

Is the story over? No.

The above statements only hold for general cases. There are many corner cases in the real world that our college courses never covered. CPUs are marvels of modern engineering and industry, and they have many corner cases that defy our common sense. So, different register names can sometimes significantly impact performance. I have collected these corner cases into four categories.

Note, the rest of the article only talks about Intel micro-architectures.

Special Instructions

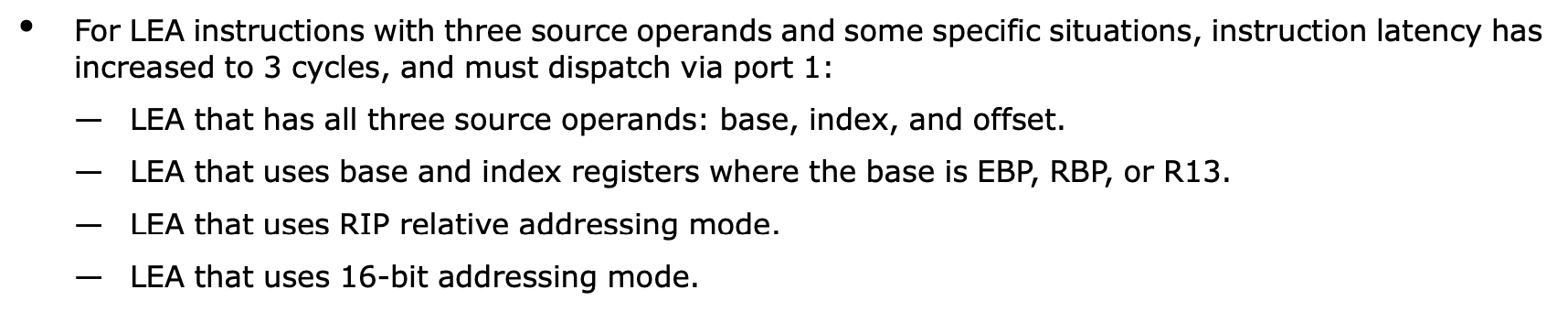

A few instructions execute more slowly with certain logical registers due to micro-architecture limitations. The most famous one is LEA.

LEA was designed to leverage the complex and powerful x86 addressing mode for wider applications, such as arithmetic computations, which requires fewer registers for intermediate results than arithmetic instructions. However, certain forms of LEA can only be executed on port 1, and those LEA forms with lower ILP and higher latency are called slow LEA. According to the Intel optimization manual, using EBP, RBP, or R13 as the base address will make LEA slower.

Although compilers could assign other registers to the base address variables, sometimes that is impossible during register allocation, and there are other forms of slow LEAs that cannot be improved by register selection. Hence, in general, compilers avoid generating slow LEAs by (1) replacing LEA with equivalent instruction sequences that may need more temporary registers, or (2) folding LEA into the addressing modes of instructions that use it.

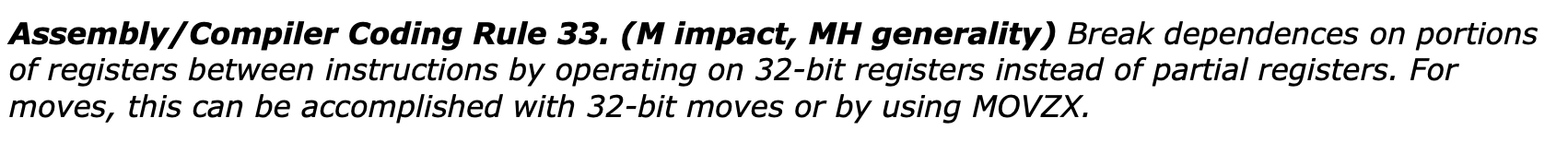

Partial Register Stall

Most types of x86 registers (e.g., general-purpose registers, FLAGS, and SIMD registers) can be accessed at multiple granularities. For instance, RAX can be partially accessed via EAX, AX, AH, and AL. Accessing AL is independent of AH on Intel CPUs, but reading EAX content that was written through AL has significant performance degradation (5-6 cycles of latency). Consequently, Intel suggests always using registers with sizes of 32 or 64 bits.

MOV AL, BYTE PTR [RDI]

MOV EBX, EAX // partial register stall

MOVZX EBX, BYTE PTR [RDI]

AND EAX, 0xFFFFFF00

OR EBX, EAX // no partial register stall

MOVZX EAX, BYTE PTR [RDI]

MOV EBX, EAX // no partial register stallPartial register stall is relatively easy to detect on general-purpose registers, but similar problems can occur on FLAGS registers and are much more subtle. Certain instructions like CMP update all bits of FLAGS as execution results, but INC and DEC write to FLAGS except for CF. So, if JCC directly uses FLAGS content from INC/DEC, JCC could have a false dependency on unexpected instructions.

CMP EDX, DWORD PTR [EBP]

...

INC ECX

JBE LBB_XXX // JBE reads CF and ZF, so there would be a false dependency from CMPConsequently, on certain Intel architectures, compilers usually do not generate INC/DEC for loop counter updates (i.e., i++ in for (int i = N; i != 0; i--)) or reuse the FLAGS produced by INC/DEC for JCC. On the other hand, this increases code size and can cause I-cache issues. Fortunately, Intel has fixed the partial register stall on FLAGS since SandyBridge

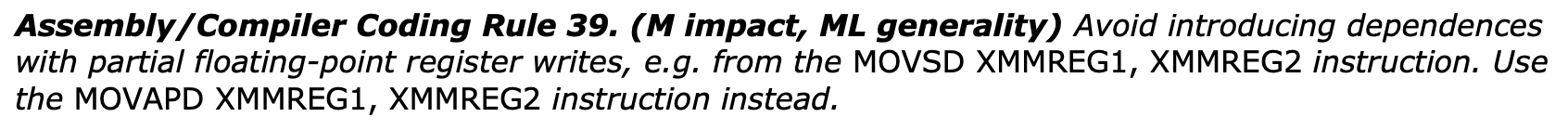

So far, you may already think of SIMD registers. Yes, the partial register stall also occurs on SIMD registers.

But partial SIMD/FLAGS register stall is an instruction selection issue instead of register selection. Let’s finish this section and move on.

Architecture Bugs

Certain Intel architectures (SandyBridge, Haswell, and Skylake) have a bugLZCNT, TZCNT, and POPCNT. These three instructions all have 2 operands (1 source register and 1 destination register), but they differ from most other 2-operand instructions like ADD. ADD reads its source and destination, then stores the result back to the destination register; such ADD-like instructions are called RMW (Read-Modify-Write). LZCNT, TZCNT, and POPCNT are not RMW—they just read the source and write back to the destination. Due to some unknown reason, those Intel architectures incorrectly treat LZCNT, TZCNT, and POPCNT as normal RMW instructions, causing them to wait for computing results in both operands when in fact only waiting for the source register to be ready is necessary.

POPCNT RCX, QWORD PTR [RDI]

...

POPCNT RCX, QWORD PTR [RDI+8]Assume the above code is compiled from an unrolled loop that iteratively computes bit counts on an array. Since each POPCNT operates on a non-overlapping Int64 element, the two POPCNT instructions should execute completely in parallel. In other words, unrolling the loop by 2 iterations should make it at least 2x faster. However, that does not happen because Intel CPUs think that the second POPCNT needs to read RCX, which was written by the first POPCNT. So the two POPCNT instructions never run in parallel.

To solve this problem, we can change the POPCNT to use a dependency-free register as the destination, but that usually complicates the compiler’s register allocation too much. A simpler solution is to force triggering register renaming on the destination register via zeroing it.

XOR RCX, RCX // Force CPU to assign a new physical register to RCX

POPCNT RCX, QWORD PTR [RDI]

...

XOR RCX, RCX // Force CPU to assign a new physical register to RCX

POPCNT RCX, QWORD PTR [RDI+8]Zeroing RCX by XOR RCX, RCX or SUB RCX, RCX does not actually execute XOR or SUB operations—these instructions just trigger register renaming to assign an empty register to RCX. Therefore, XOR REG1, REG1 and SUB REG1, REG1 do not reach the CPU pipeline stages beyond register renaming, which makes the zeroing very cheap even though it increases CPU front-end pressure slightly.

SIMD Registers

Intel provides impressive SIMD acceleration via the SSE/AVX/AVX-512 ISA families. But there are more tricks in SIMD code generation than on the scalar side. Most of the issues involve not only instruction/register selection but also instruction encoding, calling conventions, hardware optimizations, and more.

Intel introduced VEX encoding with AVX, which allows instructions to have an additional register to make the destination non-destructive. This is beneficial for register allocation on new SIMD instructions. However, Intel created a VEX counterpart for every old SSE instruction, including non-SIMD floating-point instructions. This is where things get complicated.

MOVAPS XMM0, XMMWORD PTR [RDI]

...

VSQRTSS XMM0, XMM0, XMM1 // VSQRTSS XMM0, XMM1, XMM1 could be much fasterSQRTSS XMM0, XMM1 computes the square root of the floating-point number in XMM1 and writes the result to XMM0. The VEX version VSQRTSS requires 3 register operands and copies the upper 64 bits of the second operand to the result. This gives VSQRTSS an additional dependency on the second operand. For example, in the above code, VSQRTSS XMM0, XMM0, XMM1 has to wait for data to be loaded into XMM0, but that is useless for scalar floating-point code. You might think that we can have compilers always reuse the 3rd register in the 2nd position, VSQRTSS XMM0, XMM1, XMM1, to break the dependency. However, that does not work when the 3rd operand comes directly from a memory location, like VSQRTSS XMM0, XMM1, XMMWORD PTR [RDI]. In that situation, a better solution is to insert XOR to trigger register renaming for the destination.

Programmers often assume that using 256-bit YMM registers should be 2x faster than 128-bit XMM registers. Actually, that is not always true. Windows x64 calling conventions define XMM0-XMM15 as callee-saved registers

One More Thing

Looking back at the code at the very beginning of this post, it does not seem to fall into any of the above categories. But the 2 lines of code may still run with different performance. In the code section below, the comments show the instruction encoding, which is the binary representation of instructions in memory. We can see that using ADD with EAX as the destination register is 1 byte shorter than the other, giving it higher code density and making it more cache-friendly.

ADD EAX, 0xffff0704 // 05 04 07 FF FF

ADD EBX, 0xffff0704 // 81 C3 04 07 FF FFConsequently, even though selecting EAX or other registers (like EBX, ECX, R8D, etc.) does not directly change ADD’s latency/throughput, it can still affect overall program performance.